In early June 1940 British forces in Norway were in a dangerous position: the success of the German Blitzkrieg in the West had already wiped out all Allied armies in Belgium, France and the Low Countries. Dunkerque had succesfully been evacuated in the previous days, but now the United Kingdom was facing the serious threat of a German invasion. It was thus necessary to bring all units and men in Norway back home and evacuate the scandinavian country.

|

| No. 812 Sqn Swordfish over HMS Glorious in 1937 |

Two convos of troopships were organized and sailed on 5 June. The two aicraft carriers HMS Glorious and HMS Ark Royal were tasked with providing air protection for the evacuating ships.

In the early hours of 8 June, Glorious asked permission to Vice Admiral Aircraft Carriers aboard Ark Royal to proceed independently to Scapa Flow.

Two reasons are cited by different sources for this request: one of them is a supposed fuel shortage, while the second states that Glorious' captain, Guy D'Oly-Hughes, intended to hold a court-martial against his Air Commander, J.B. Heath, who had refused to carry out an attack on shore targets for which his Swordfish were unsuited.

The request was granted and the aircraft carrier parted from the Ark Royal at 03:00, with two escorting destroyers, HMS Ardent and HMS Acasta.

|

| HMS Acasta |

Only 10 months earlier, the aicraft carrier HMS Corageous had been torpedoed and sunk off Ireland, while independently carrying out an anti-submarine patrol with the escort of two destroyers. The sinking prompted the Admiralty to withdraw all aircraft carriers from such missions. After that loss, it might have been imagined the utmost care would have been taken to guarantee effective escort for fleet carriers.

During the previous two months of operations off Norway, warships and convoys had crossed the water from Scotland to the scandinavian coast encountering little reaction from German surface units. The Admiralty was thus lulled into the misplaced assumption that the only threat were the Uboats. This sense of complacency allowed the Royal Navy to think an aircraft carrier could safely travel in the Norwegian Sea with only a small escort.

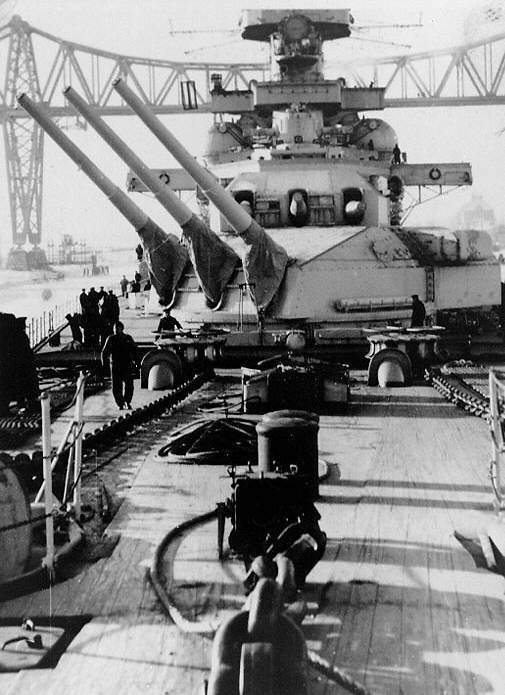

Moreover, the Admiratly was unaware of the fact the German surface units were at sea: the modern battlecruisers Scharnorst and Gneisenau had left Kiel on 4 June , and were operating in Norwegian waters with the task of attacking the British convoys.

|

| Gneisenau (left) , Scharnorst (right) and Admiral Hipper (center) in port, probably Trondheim, 1940 |

At 15.46, Gneisenau and Scharnorst were in position 69°00 N, 03°10' F, steaming at 19 knots on course 330°, when they spotted Glorious' funnel. The two battlecruisers increased speed, Gneisenau making 30 knots and Scharnorst 29 due to some minor boiler troubles.

HMS Ardent was ordered to break from the main formation and investigate the sighting. In the meantime, five Swordfish were prepared onboard the aicraft carrier, but reaction aboard Glorious was slow as it took 20 more minutes for action stations to be sounded, at 16:20.

The destroyer approached the unidentified vessels flashing a challenge on her searchlight, but she was taken under fire by Gneisenau at 16:27 and by the Scharnorst at 16:30, from a distance of about 16000 yards. The Ardent fired a volley of torpedoes, one of which was seen passing close ahead of the Scharnorst. The destroyer then retreated and started laying a smoke screen. She manged to achieve one hit with her 4.7-inch guns, but was then riddled by return fire from the battlecruisers' secondary armament of 5.9-inch batteries, and sank at about 17:25.

Gneisenau's slightly superior speed made her slowly overhaul the Scharnorst during the battle, putting the sister ship around 5000 yards on her port side. The latter opened fire against the Glorious at 16:32, with Gneisenau firing its first salvo at 16:46.

The aircraft carrier received its first hit at 16:38, from Scharnorst's third salvo. The flight deck was penetrated, and the 283-mm shell burst in the upper hangar starting a large fire. Splinters also pierced a boiler casing and smoke entered the air intakes, causing a brief drop in steam pressure from two boilers.

A second hit was suffered at 16:56, when the bridge was wrecked and all personnel on it, including, the captain, killed.

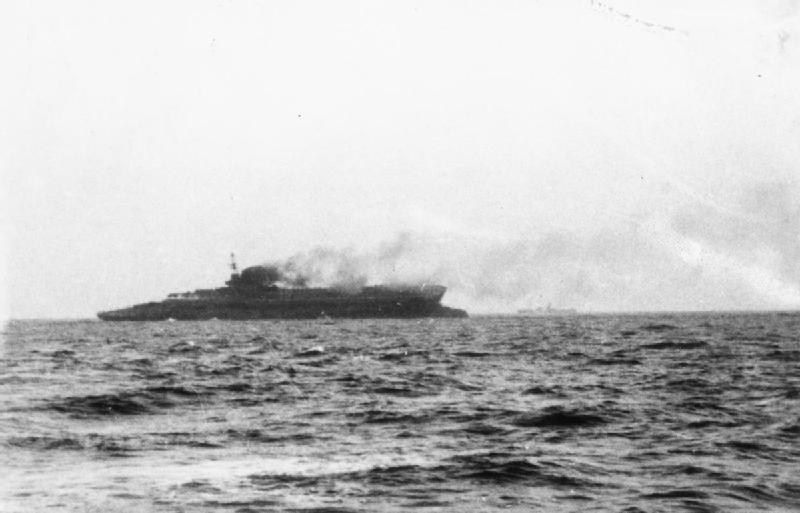

The smoke screen laid by the two destroyers effectively conceiled the Glorious, forcing the Germans to cease fire until 17:20. As soon as the British became visible again, the aircraft carrier suffered further hits in the center engine room, began to lose speed, took a heavy list to starboard and commenced a slow circle to port.

By 17:40 HMS Glorious was a floating wreck and the Germans ceased fire, focusing on the last remaing vessel, HMS Acasta.

The last survivor fought desperatly and gallantly to protect the aircraft carrier. At 17:30 the destroyer broke off from the smoke screen, passed ahead of Scharnorst and positioned itself to the battlecruiser's starboard side, firing its torpedoes in two four-tube salvos. On of them hit the Scharnorst below the aft main turret, causing heavy damage and casualties. As the Ardent, Acasta

was taken under heavy fire from the enemy as she turned away, and was riddled by several hits until both battlecruisers ceased fire at 18:08, HMS Acasta also being reduced to a wreck.

|

| The smoke screen laid by Ardent and Acasta as seen from the Scharnorst |

Ten minutes later, at 18:15, the Germans altered course for Trondheim, with Scharnorst badly damaged and able to to steam at no more than 20 knots.

Glorious finally sank at 18:10, leaving 900 men in the water. The admiralty remained ignorant of the sinking until the Germans triumphantly broadcasted it on 9 June. Search and rescue missions were mounted, but given the rough seas and cold weather most of the survivors died at sea.

The Nowegian merchant Borgund picked up 37 survivors, two of whom subsequently died. They were landed at Thorshaven and then came back to the UK. Another Norwegian ship, Svalbard II, rescued five survivors but was forced to come return to Norway, were the four men still alvie were made POW. Only one man survived from HMS Ardent, none from Acasta.

Total loss from the three warships were 1,519 men.

Glorious finally sank at 18:10, leaving 900 men in the water. The admiralty remained ignorant of the sinking until the Germans triumphantly broadcasted it on 9 June. Search and rescue missions were mounted, but given the rough seas and cold weather most of the survivors died at sea.

The Nowegian merchant Borgund picked up 37 survivors, two of whom subsequently died. They were landed at Thorshaven and then came back to the UK. Another Norwegian ship, Svalbard II, rescued five survivors but was forced to come return to Norway, were the four men still alvie were made POW. Only one man survived from HMS Ardent, none from Acasta.

Total loss from the three warships were 1,519 men.

Sources:

www.hmsacasta.co.uk

List of casualties from HMS Acasta: http://www.hmsacasta.co.uk/crew%20list.html

HMS Glorious technical details: