The history of the nachtjad begins in late 1939-early 1940, when the Bomber Command, frustrated by the severe losses sustained during daylight raids over Germany, decided to divert its aircraft to night operations. At that time, the Luftwaffe had operational three Staffeln for night fighting duties :

- 10. (Nacht)/JG 26

- 10. (Nacht)/ZG 26

- 10.(Nacht)/JG 53.

This unit were tasked with defending the Reich airspace collaborating with searchlights and flak batteries on the ground. Given the nature of the job, victories were rare, while losses for flying accidents were extremely high. Also, the Luftwaffe was not particularly interested in night interception, as the Wermacht was on the offensive and the danger of night bombing was considered minimal. In december 1939 the two night staffeln of JG 26 and ZG 26 were joined into a single unit, with the add of 11.(Nacht)/LG 2. This led to the creation of the first night Gruppe, designated IV(Nacht)/JG 2.

Victories continued to be rare: between April and May 1940 three kills were recorded, but they were actually scored at dusk or dawn, rather than night. On 17 July, 1940, it was decided to create the 1. Nachtdivision, under the command of Major Josef Kammubher, former Geschwaderkommodore of KG 51. With Kammubher's leaderships, the organization of night flying units was entirely revolutionized, and at the end of 1940 it is so composed:

- I., II. II/NJG 1 equipped with Bf-110 C-1

- 10./NJG 1 equipped with Bf 109D

- 1. and 2./NJG equipped with Ju-88C, Do 17Z and Bf 110C

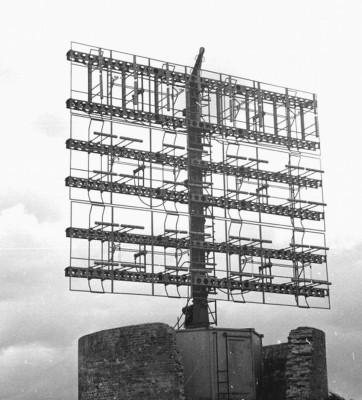

The main difficulty for night pilots was to catch and attack the enemy in total darkness, therefore Kammhuber and General Wolfgang Martini set up "enlighted" sectors, were searchlights on the ground operated in order to illuminate specific areas of the sky. In addition, they ordered development and implementation of radar installation, especially the FuMG62 Wurzburg and the FuMG80 Freya.

|

| Freya radar antenna |

Interception were still entirely handled by the pilots in the air: ground control was still not available, so what the pilots could do was to wait near the illuminated ares, hoping to spot a bomber silhouetted against the sky, giving full speed and trying to attack before the target disappeared into the darkness. Soon the British realized the it was sufficient to avoid the searchlight belts to escape interception, therefore Luftwaffe victories redscended to the minimum. The system, known as Helle Nacthjagd (illuminated nightfighting) became clearly ineffective. Kammuhuber's reaction led to creation of the Dunkle Nachtjagd (dark nightfighting), where the fighter where assisted by Ground Control (GCI), placed behind the searchlight belts and based on Freya and Wurzburg radars.

Around the most important cities, the "dark" and "enlighted" methods were combined into the Konaja (Kombinierte Nachtjagd, combine nightfighting), which operated in close contact with Flak units on the ground. At the end of 1941 the 1. Nachtdivision was renamed XII FLiegerkorps. Its units were almost entirely equipped with the Messerchmitt Bf 110. The exception was represented by I./NJG 2, which operated Ju 88C and Do 17Z in long-range offensive mission, known as "Ferne nachtjagd" (ferne meaning far). These missions proved to be extremely costly in terms of losses, but were also highly successful, both in terms of bombers shot down and diverted British resources.

The pilots of I./NJG 2 used to follow Bomber Command bombers on their way back home, waiting until they reached their airfields and attacking them at the most vulnerable moment, while landing or circuiting. The Germans also dropped bombs on the airfields, creating chaos and confusion, as the gunners on the ground couldn't fire back fearing to hit their fellow bombers. The unit scored 141 confirmed victories, and also forced the RAF to stop night flying training in East Anglia, Lincolnshire and Yorkshire. At the end of the year, however, the units was transferred to North Africa, to mount long range missions against Malta.

The end of 1941 also saw the introduction of the Himmelbett interception system. It consisted of a series of radar stations, organized in a continuos belt running from central France to Denmark. Each radar covered an area of about 32 km long (N-S) and 20 km wide (E-W). This areas were known as boxes, and operated with a complex mechanism of electronic devices and searchlights. A Freya radar with a 100-km range was used to pick up targets on their way to the Reich, assistes by a Wurzburg radar who gave indication of speed and altitude of the incoming bombers. A second Wurzburg was manned by ground controllers to vector the fighter within 3-400 m from the target. There was also a "master searchlight" directed by the first Wurzburg, supported by a number of manually directed searchlights. Each box had is own assigned night fighter, with one backup.

It was a complex and elaborated method which had its own advantages and drawbacks. Since British bombers used to fly indipendent routes towards their targets, it was theoretically possibile to intercept every single bomber. Once the Freya and Wurzburg radars had determined speed and altitude, the searchlights illuminated the plane: at the same time, ground controllers gave the pilots instruction to intercept the bomber. Once reached 3-400 m, the night crews were on their own and attacked by visual means.

The pitfalls on this method were clear from the very moment it was implemented. It required a huge amount of resources, because each box had at least three radars, one GCI control station, a number of searchlights and limited time to conclude the interception. In fact, GCI on the ground could only intercept a bomber within their own boxes.

In addition to that, the pilots were still blind on the air, relying entirely on the instrucionts from the ground. This meant that chances of successful interception depended on the experience and skill of the ground controller.

The Luftwaffe tried to give night pilots their own "night eyes" by mounting aboard Do 17Z the "Spanner Anlage", an infrared device which gave poor results.

The solution came in the form of the FuG 202 Liechtenstein B/C radar, which had a minimun range of 200 m and a maximum of 3-4 km. Once the GCI had vectored the fighter in the proximity of the bomber, the crews could pick it on their radar and chase it on their own.

Pilots were initially reclutant to mount to heavy radar antennas on their planes, but they changed their mind when victories started to rise. However, it took almost a full year before the Liechtenstein B/C could be distributed to all Gruppen, as the conversion center of Diepensee had a capability of just 5-6 aircraft per week.

It was a complex and elaborated method which had its own advantages and drawbacks. Since British bombers used to fly indipendent routes towards their targets, it was theoretically possibile to intercept every single bomber. Once the Freya and Wurzburg radars had determined speed and altitude, the searchlights illuminated the plane: at the same time, ground controllers gave the pilots instruction to intercept the bomber. Once reached 3-400 m, the night crews were on their own and attacked by visual means.

The pitfalls on this method were clear from the very moment it was implemented. It required a huge amount of resources, because each box had at least three radars, one GCI control station, a number of searchlights and limited time to conclude the interception. In fact, GCI on the ground could only intercept a bomber within their own boxes.

In addition to that, the pilots were still blind on the air, relying entirely on the instrucionts from the ground. This meant that chances of successful interception depended on the experience and skill of the ground controller.

The Luftwaffe tried to give night pilots their own "night eyes" by mounting aboard Do 17Z the "Spanner Anlage", an infrared device which gave poor results.

/images/1-Bf-110E-9.NJG1-(G9+HT)-Schleswig-1941-01.jpg) |

| 9./NJG 1, Schleswig, 1941 |

The solution came in the form of the FuG 202 Liechtenstein B/C radar, which had a minimun range of 200 m and a maximum of 3-4 km. Once the GCI had vectored the fighter in the proximity of the bomber, the crews could pick it on their radar and chase it on their own.

Pilots were initially reclutant to mount to heavy radar antennas on their planes, but they changed their mind when victories started to rise. However, it took almost a full year before the Liechtenstein B/C could be distributed to all Gruppen, as the conversion center of Diepensee had a capability of just 5-6 aircraft per week.

No comments:

Post a Comment